In her own words...

"To the Editors"

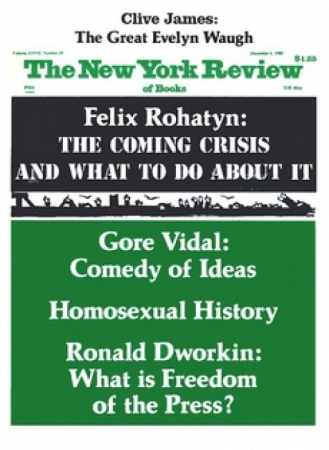

1980

Denis Donoghue's patient explanation of the deconstruction fever [NYR, June 12] so rife not only in universities but also in Soho lofts and midtown cocktail parties, really makes it easier for us all, at least for me, to close the dossier and file it away among earlier forgettable fads. I would not, however, be inclined to include the surrealism of the Thirties in this list. In fact I find it grievous that Mr. Donoghue is so reminded. And his quote from William Empson's poem to the effect that the surrealists enjoyed (my italics) "a nightmare handy as a bike" is sadly irresponsible. Do these two men realize that the “nightmare” was the aftermath of the world's most lethal war? And that recovery seemed not only slow but impossible to a group of enraged young people in revolt against a society that had sent a number of them to fight that war?

we discover their most hidden virtues as well as their secret sounds, shapes and ideas.

Then language becomes oracle and hands us a thread, however tenuous it be, to guide us

inside the Babel of our mind.

The writings of these men--precursors Raymond Roussel (ask Robbe-Grillet), Jacques Vache (a suicide), and their suite: Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, André Breton, Antonin Artaud, Paul Eluard, Max Ernst, René Crevel (a suicide), Georges Bataille, to name a few--were not solemn but were often exuberant, ironic, even hilarious. Obviously, the hilarity served to draw a merciful veil over their despair.

Dorothea Tanning

New York City

About this work

This letter to the editors was published in the The New York Review of Books, December 4, 1980, p. 57, in response to Denis Donoghue's review, "Deconstructing Deconstruction," in the June 12, 1980 issue.